No shortcuts to organizing

Jane McAlevey’s No Shortcuts has been read by hundreds of DSAers and discussed in online book discussion groups this summer. She recently spoke with Puya Gerami to answer frequently raised questions. The interview has been slightly edited for space.

Jane McAlevey’s No Shortcuts has been read by hundreds of DSAers and discussed in online book discussion groups this summer. She recently spoke with Puya Gerami to answer frequently raised questions. The interview has been slightly edited for space.

Union membership, strike frequency, and working-class living standards have plummeted over the last four decades. How do you explain the existential crisis facing the labor movement today?

First, there is the very real pressure of sophisticated union-busting in the U.S. The union-avoidance industry here is unique and gets away with campaigns of intimidation and terror that don’t exist elsewhere, outside of countries with dictatorships or seriously authoritarian regimes.

Union-busting drove globalization. There was simply no reason for the global trade regime, which emerged in the 1970s and then took off in the 1980s and 1990s, except to bust unions by shifting jobs to countries where workers lack basic rights, let alone freedom in the workplace. This was a clear strategy to get rid of unions by getting rid of the unionized segment of the private sector. That way capitalists wouldn’t have to share the larger portion of the wealth that unionized workers forced them to starting in the 1930s.

As the corporate elite doubled down on union-busting through globalization, the trade union movement, as well as the broader progressive movement, failed to understand that the proper choice was not to retreat from organizing, but to build an even more robust organizing effort, similar to that of the 1930s. We went backward in our understanding of power. Unions shifted to a mobilizing approach: taking shortcuts from the hard work of building supermajority participation, relying instead on lawyers, research, and communications to wage tactical warfare that only succeeds when it complements the more fundamental work of deep organizing inside and outside of the workplace.

You distinguish between three approaches to social change: advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing. Why is it so crucial that leftists embrace organizing?

To understand the differences, we must begin with a key question: what is your theory of power?

Both advocacy and mobilizing subscribe to an elite theory of power. Because they seek merely to tinker on the margins rather than make structural change, these approaches rely on a handful of people, like lawyers and media specialists. For those of us who want to seriously challenge the status quo, an elite theory of power isn’t going to work.

It’s important that we understand the difference between the limits of advocacy and the limits of mobilizing.

In the advocacy approach, there’s really no pretense that people need to be involved at all. Members can write a check to an organization, which hires staff and take care of business. That’s not going to work if we want to change society in fundamental ways.

How about the mobilizing approach? Some movement people invite folks to open meetings or direct actions and call that organizing. But it’s not. It’s self-selecting work, because it involves mobilizing people who already agree with us. We don’t have enough power in this country to rely just on those who show up at our events.

The difference between mobilizing and organizing becomes clear during workplace organizing—say, planning a strike—because we’re trying to build to 100% participation, which means total unity. To achieve 95-100% participation requires us to talk to every single person. We spend most of our time talking with workers who absolutely do not want to talk with us—that’s the hard and important work of organizing, engaging people who don’t want to be engaged. The organizing approach means we simply can’t be sloppy about focusing on those who agree with us, because the whole point is to expand the base so we can build greater absolute power. In every campaign, a third of the workers might be easy to mobilize because they’re pissed off at the boss and want to do something about it—but the objective in organizing is to build a supermajority.

I think that’s a metaphor for how we need to organize a mass movement. Organizing relies on the one strategic advantage we have on the Left: large numbers. Converting the rhetoric of “We are the 99%” into a mass movement takes skill, discipline, and intentional strategy. We have to punch way beyond the fraction of people who already agree with us on most issues if we’re going to contend for real power.

The key to this vision of deep organizing is a very particular definition of leadership identification—one that many on the Left don’t seem to share. What are leaders?

Leaders are those who have the capacity to bring large numbers of people with them into the process of social change. Many don’t have formal titles or positions. The fundamental definition of their leadership is that other people follow them.

The word follow makes some toes curl, but we have to grapple with it. If our issues are urgent, and we’re serious about building a supermajority, we don’t have time to prioritize every person equally. Deep organizing implies that there are always people who have the natural capacity to bring along much larger numbers of people through fearful situations—that isn’t everybody.

If we want to build power, we have to understand the difference between leadership identification and leadership development. When most people talk about leadership development, they’re talking about measuring someone’s commitment to the work. But true leadership identification means identifying ordinary people with a high capacity to lead others. Leadership development is most effective when we practice accurate identification, because then we’re prioritizing the organic leaders who already have a high capacity to move the people around them into action.

The usual approach is to identify people who have attended multiple events and encourage them to take on increasing leadership responsibilities in the organization. But that’s very different from identifying people in the ranks who already demonstrate high capacity for leadership, but who may not be the least bit interested in getting involved at first. We need to have hard conversations with these people to help them come to understand that mass collective action is the only solution to any number of crises in their lives. We must identify them and then test or assess whether they are indeed organic leaders. These organic or natural leaders are a more diverse group, from a race/ethnicity and traditional gender view, which is another reason we have to prioritize real leadership identification.

Right now, DSA is a self-selecting formation that primarily practices mobilizing. But we aspire to develop a mass movement that practices structure-based organizing. How do we apply the effective organizing methodology you describe to our goal of building DSA?

I believe there are endless opportunities for DSA chapters as initially self-selecting formations to play a serious role in building power in their communities.

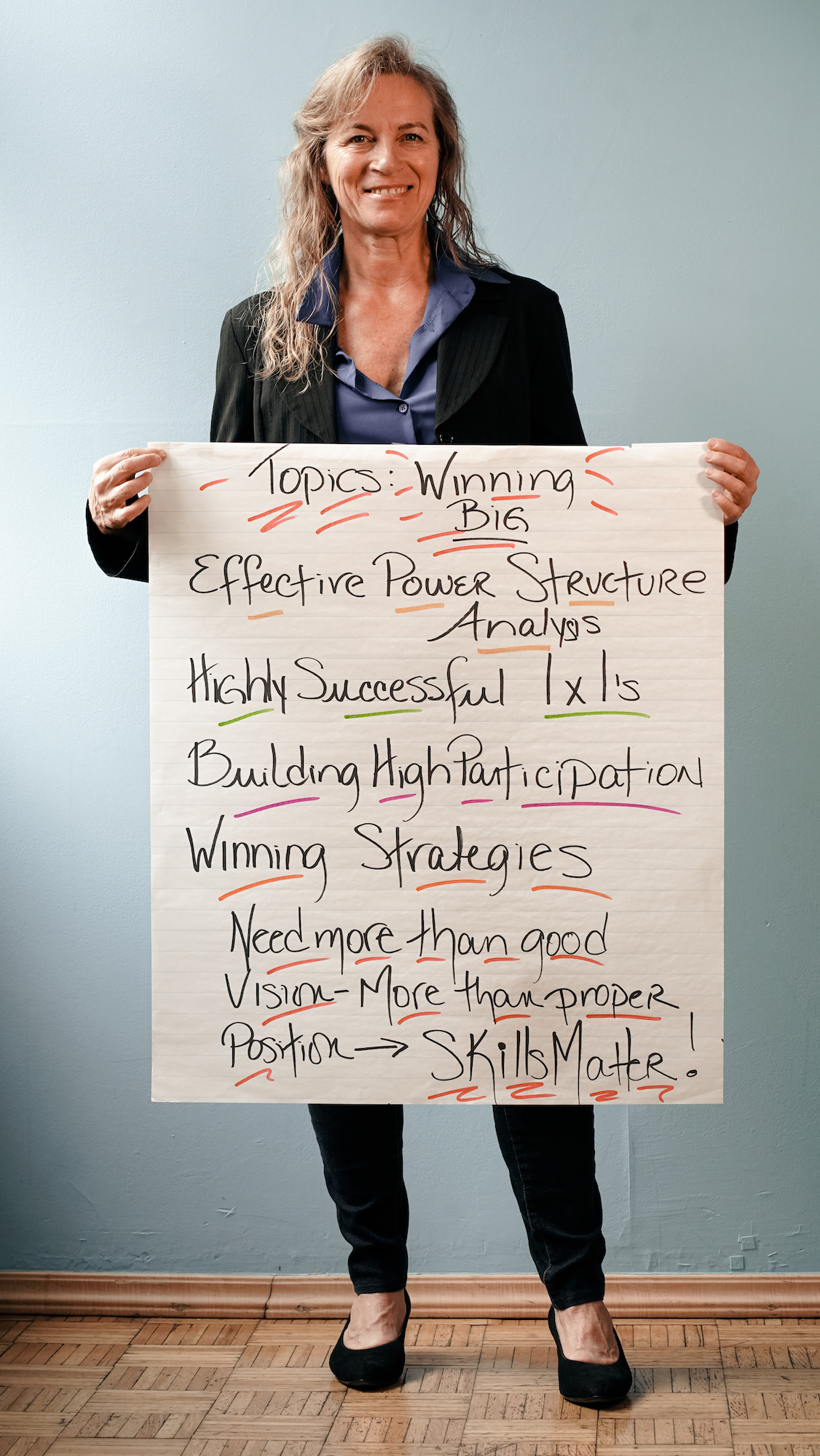

Chapters are structured on a geographic basis. Their first task is to understand who’s around them by completing a power-structure analysis of their area. This requires a collective research project to chart the universe of existing organizations—the infrastructure of a potentially left movement with a structure-based, measurable, supermajority reach. Who are the unions, the community organizations, the houses of faith?

DSA chapters must figure out how to create bounded constituencies where they don’t seem obvious at first glance. For example, let’s say there’s a big, active union local or community organization or synagogue in your community. Chapters have to identify the universe of total members in each institution and then practice leadership identification. Who are the informal leaders in each institution? How can we recruit them and the people they lead to join our campaigns and participate in DSA? Who from DSA already has a connection to these groups and institutions, either directly or indirectly? We don’t know until we actually ask every single DSA member—it is always surprising how many connections ordinary people have to existing groups.

Finally, chapters must prioritize a limited number of campaigns, match up with existing organizations in the community, and make a strategic plan. Campaigns offer the opportunity to run structure tests—mini-campaigns in which we move an issue within a bounded constituency in order to identify and confirm organic leaders, facilitate unity through political education, and ultimately advance our vision by building from minority support to supermajority support. All groups serious about change have to use lots of campaigns with a clear yes/no, win/lose outcome, otherwise, we have no idea if the work we are doing matters.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America