Looking to History for Labor’s Future

As labor continues to face enormous challenges, it’s worth remembering that U.S. workers, despite some of the most violent and vicious repression in the Western world, have never accepted the domination of the upper classes. Domestic class struggle is as old as Bacon’s Rebellion (1676-7), when white and black colonial servants joined together against their common oppressor—Virginia’s ruling class.

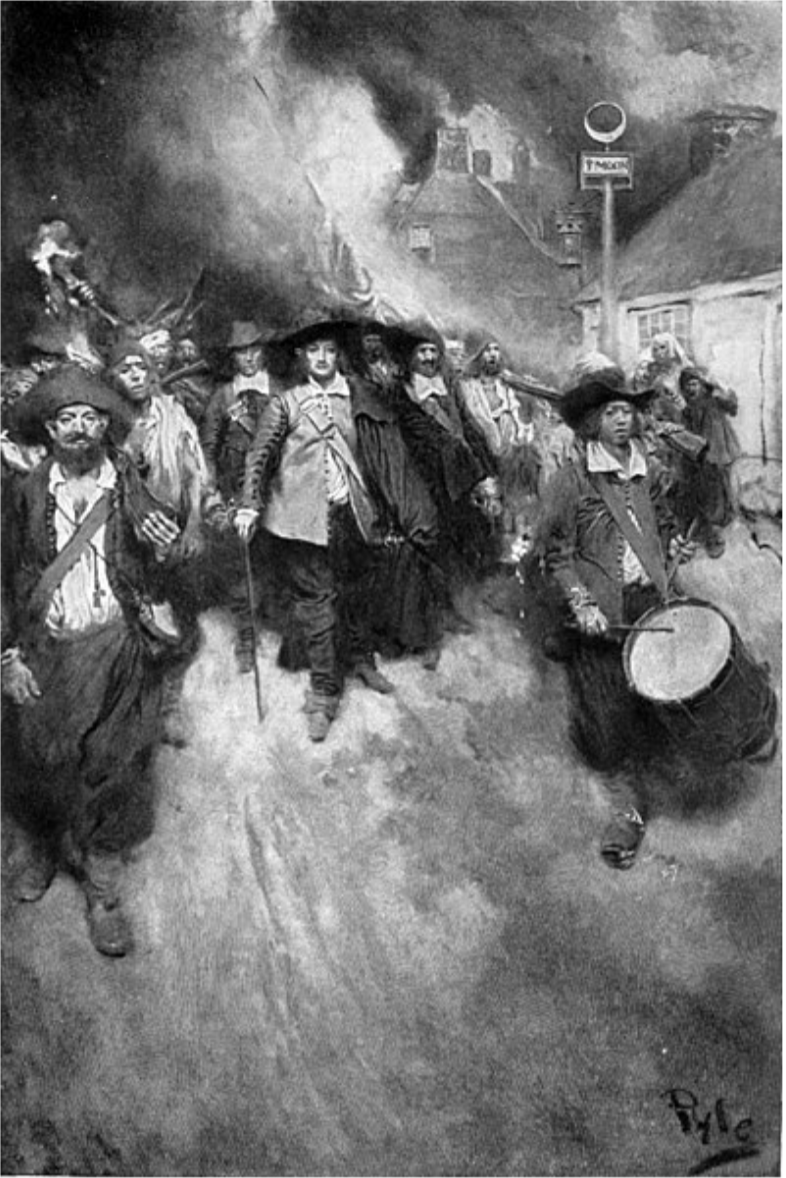

Bacon’s Rebellion: Howard Pyle painting (1905) Burning of Jamestown (Harper’s Encyclopedia, 1905)

In the nineteenth century, Henry David Thoreau argued a case for resisting government injustices such as slavery with civil disobedience, but workers added another dimension—a private-sector disobedience against employers’ injustices such as poverty wages, inhumane working conditions, no job security, and so on. As the century wore on, this opposition assumed various forms: strikes and boycotts, slowdowns, and rallies. Employers’ friends in the criminal justice system often charged workers with violation of the law when they joined to disobey the boss. But working people persevered in their search for justice.

Labor newspapers carried the message of workers and labor unions to other workers and to the public at large, and they multiplied in the decade following Thoreau’s death in 1862. In 1867, unions banded together organizationally to create the local Central Labor Union where representatives met and discussed common concerns, and eventually their delegates met in larger groups–most successfully in the American Federation of Labor (AFL), formed in 1886, which affiliated chiefly craft (skilled) workers’ unions.

The unions faced a rigged system. As newspaper magnate Edward W. Scripps said in 1912, “We, the employers… have the jobs to give or withhold, the capital to spend or not in production, for wages, for ourselves; We have the press to state our case and suppress theirs; we have the bar and the bench, the legislature, the governor, the police and the militia.”

Great labor-corporate clashes in the 1890s seemed to confirm the invincibility of the rigged system. Yet, a coalition of forward-looking labor unions and progressive elements of the rising professional middle class began to form. The “good government” progressives stemmed from Thoreau’s rather individualistic approach and pushed on to demand direct-democracy measures– initiatives, referenda, and reform–and anti-trust actions, pointing toward a greater democratization of government, while union forces strove through collective action to strengthen workers’ power, pointing toward industrial democracy. Slowly, the participants found in each other’s aims elements that supported their own. Some in each camp became socialists–Eugene Debs and many others in labor, Jane Addams and others among progressives–in the effort to push beyond the aim of civilizing Capital to create a social democracy.

Some unions–notably the United Mine Workers–opened membership to African Americans and others to women. Union memberships exploded from 300,000 in 1898 to 1.65 million in 1904. In 1905 a radical industrial (as opposed to craft-based) union–the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)–arose to challenge the status quo, all with professional middle-class assistance. By 1912, the progressive Louis Brandeis persuaded the Woodrow Wilson to maintain a friendly policy position toward labor, and a Socialist Party member, Victor Berger, had been elected to the House of Representatives in 1910.

The labor shortage caused by the U.S. entry into the First World War helped cooperative pro-war (mainly AFL) unions. AFL membership grew from 2.7 million in 1916 to 4 million in 1917, while the anti-war IWW suffered attacks by the government. Left-wing labor hopes rose at war’s end, lifted by the apparent victory of a workers’ revolution in Russia. But the future wasn’t as bright as it appeared. A wave of strikes followed the war and, despite their defeats, aroused a fierce anti-labor Red Scare campaign by conservatives, including an “open shop” (non-union) counter-attack that reduced union membership to 7% of the workforce by 1930 and aided the rise of the Ku Klux Klan to 4.5 million members.

Still, labor and the Left didn’t disappear, and the economic collapse of the Great Depression gave them new life. As unemployment rose to 25%, and workers realized that they were not unemployed because of personal failures, working people increasingly saw unions as an ally.

The New Deal years of the 1930s produced the greatest series of reform and liberation since the abolition of slavery, and labor unions played a militant role, beginning with left-led organizing campaigns. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and the Social Security Act are the best-known laws that earned labor support. The Fair Labor Standards Act also accompanied laws on job creation, poor relief, and aid to farmers. These reforms won approval because of a coalition of liberal professionals and unions, as well as the unity of various ethnic and religious groups and the Socialist Party. In this, the progressive New Deal incorporated the minimal program of both the Socialist Party and organized labor.

The Second World War— the New Deal on steroids— ended the Great Depression, and labor’s strength grew. A rolling strike of unions that were part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) forced industrialists to nearly double their initial offers to workers. But after the war, the U.S. capitalist class emerged stronger than ever and launched a counter-attack. Beginning with the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which allowed states to pass so-called “right to work” laws and other measures to weaken labor, the New Deal reform era was over.

The McCarthy Era and the Second Red Scare then plagued the country for a decade. At the behest of conservatives, the CIO expelled eleven left-led unions, thus shedding many of its dynamic activists and retaining many pragmatists, while corporations built hundreds of manufacturing plants in foreign countries. The Great Bargain between more conservative business-oriented unions and businesses themselves had been struck, and the table was set for today.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America