Passing the Torch

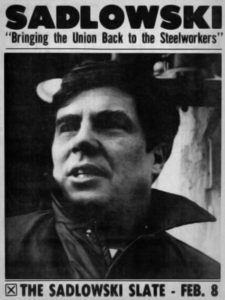

Edward Sadlowski: 1938-2018

To be a member of DSA is to inherit a socialist tradition that goes back more than a hundred years. On June 10, DSA lost a nationally celebrated comrade who united the labor radicalism of the 1930s with the social movements of the 1970s.

Edward Eugene Sadlowski grew up across the street from a union hall in South Chicago, 10 blocks from the site of the 1937 Republic Steel massacre of strikers. He followed his father and grandfather into the steel mills, dropping out of school in the 11th grade to work as an apprentice machinist in the massive U.S. Steel South Works. Carrying an oil can while walking around to talk with fellow members of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 65, he earned the nickname “Oil Can Eddie.” He was soon elected shop steward, grievance rep, and in 1964 became the youngest president of the 23,000-member local.

A believer in the legacy of socialist trade union icon Eugene Debs, Wobbly troubadour Joe Hill, and mine union firebrand John L. Lewis, Sadlowski argued for a more militant style of unionism than USW higher-ups were comfortable with. He wanted organized labor to be more confrontational to organized capital—and more welcoming to women and minority workers. He wanted the union to fight for safety and workplace rights, not just wages and pensions. At the 1968 USW convention, he broke ranks with the USW’s anti-communist leadership and denounced the Vietnam War.

He then campaigned for the leadership of USW’s largest region—District 31—with 128,000 members in 288 union locals in Chicago and Gary. It took him years (and federal intervention, after his opponents committed vote fraud) but in 1975, Sadlowski became District 31 president. The next year, he ran for president of his 1.4-million-member international union at the head of a “Steelworkers Fightback” movement.

It can be hard in 2018 to understand just how important unions were in American life even as late as the 1970s. The Steelworkers Fightback campaign captured the national imagination and was reported on by all the major media. Sadlowski was profiled in the New York Times and Rolling Stone magazine and debated his opponent on national television on NBC’s Meet the Press.

He was one of the best-known leaders of a now-mostly-forgotten left-wing insurgent movement within the labor movement of the 1970s. Those stories are told in books such as Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, by Jefferson Cowie and Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide, by Lane Windham. The insurgents mostly failed to wrest power from more conservative elements of the trade union movement. And yet many partisans of their cause stuck around and became a persistent force pushing labor leftward.

Sadlowski lost the national union election, never ran again, and spent the rest of his union career at District 31. He died at the age of 79 after a long battle with Lewy body dementia. But the torch he carried still burns. His son is deputy director of the Milwaukee teachers’ union. His daughter, an activist with the Chicago Teachers Union, defeated a Rahm Emanuel-allied incumbent to become a Chicago alderman and served as a Sanders delegate in 2016. And decades after Sadlowski became part of Chicago DSA, others are joining DSA labor branches and working groups nationwide, impatient to spark a fightback movement of the entire working class.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America