Igniting a Poor People’s Campaign

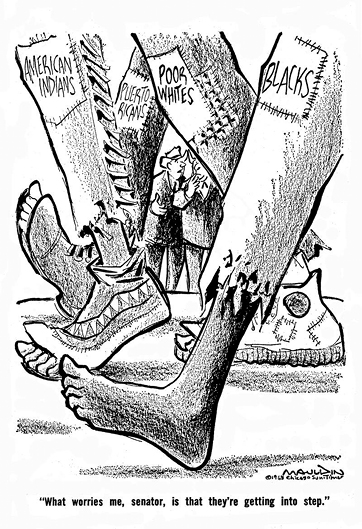

In 2018, we are awash in 50th anniversary commemorations of the events and legacy of 1968: the Tet Offensive, the My Lai massacre, the McCarthy and Kennedy campaigns, assassinations, campus occupations, police riots, and much more. One commemoration to which democratic socialists should pay particular attention, in part because their forebears had so much to do with it, may be slighted in the mainstream media: the Poor People’s Campaign launched by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The fate of that campaign is relevant to our own time, as a new Poor People’s Campaign, endorsed by DSA, gets underway to bring attention to the persistence of poverty in the United States, as well as related issues such as income inequality, mass incarceration, and voting rights.

In January 1968, King announced SCLC’s plans for a sustained campaign of mass protest and civil disobedience in Washington, DC, by an interracial coalition of poor people, to pressure the White House and Congress to launch an expanded War on Poverty. At King’s request, socialist Michael Harrington (a long-time adviser), drafted a Poor People’s Manifesto to set forth the goals of the campaign, including federal programs for full employment and low-cost housing. Part of SCLC’s strategy was to construct an encampment of poor people, known as “Resurrection City,” at the very heart of official Washington, on the National Mall between the Washington and Lincoln Monuments. But King never made it to Washington, slain on April 4 by a white supremacist sniper in Memphis, where he had gone to support a strike of the city’s sanitation workers.

Although King never joined a socialist organization, he sympathized privately with socialist ideals, and sometimes, given the right audience, proclaimed those sympathies. As he declared in a 1965 speech to a group of African American labor activists, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

Resurrection City was built in May 1968, and about 3,000 poor people of all races and regions lived there for six weeks. At SCLC’s call, 50,000 people came together in a mass march and rally on June 19 in solidarity with the campaign. Six days after the Solidarity Day rally, most of the residents of Resurrection City were arrested during civil disobedience on the Capitol grounds, and those who remained in the encampment were dispersed by police.

By 1968, the national consensus that something needed to be done for the country’s poor—sparked in part by Harrington’s influential 1962 book The Other America: Poverty in the United States—had eroded. Poor people, especially poor people of color, were increasingly viewed as responsible for their own fate, and undeserving of help from the federal government. But the demands of the original Poor People’s Campaign—for jobs, education, and housing—would have benefited a broad swath of the U.S. population: poor, working class, and middle class, black, brown, and white alike. Similarly, today the Fight for Fifteen and Medicare for All are not just programs for the poor, but for everyone not in the 1%. That’s a lesson worth learning from the ill-fated War on Poverty of the 1960s. As for the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, a brave if doomed effort overshadowed by King’s death and the other turbulent events of the year, its memory deserves its own resurrection. ϖ

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America