Closing Military Bases, Opening a New World

Why does the United States maintain troops in at least 175 countries?

In a day and age when many of us are taught to overcome prejudice and behave respectfully toward all, mainstream U.S. media and school texts still habitually portray U.S. lives as the only lives that really matter.

A plane crash that kills dozens of human beings is reported, just like a war, with the bulk of the coverage on the handful of U.S. lives lost. A U.S. military commander’s decision to bomb a village rather than subject his troops to ground combat is depicted as an act of enlightenment. The U.S. Civil War is almost universally labeled the deadliest of all U.S. wars, despite the fact that many U.S. wars have killed many more human beings — including U.S. human beings, if Filipinos were U.S. citizens during the Philippine-American war or World War II.

In a time when we are generally taught to solve our problems nonviolently, the exception for the organized mass murder of war remains. But wars are increasingly marketed not as protection from the Adolf Hitler of the Month (last month’s weapons customer), but as acts of philanthropy and benevolence, preventing massacres by bombing cities, or delivering humanitarian aid by bombing cities, or developing democracies by bombing cities.

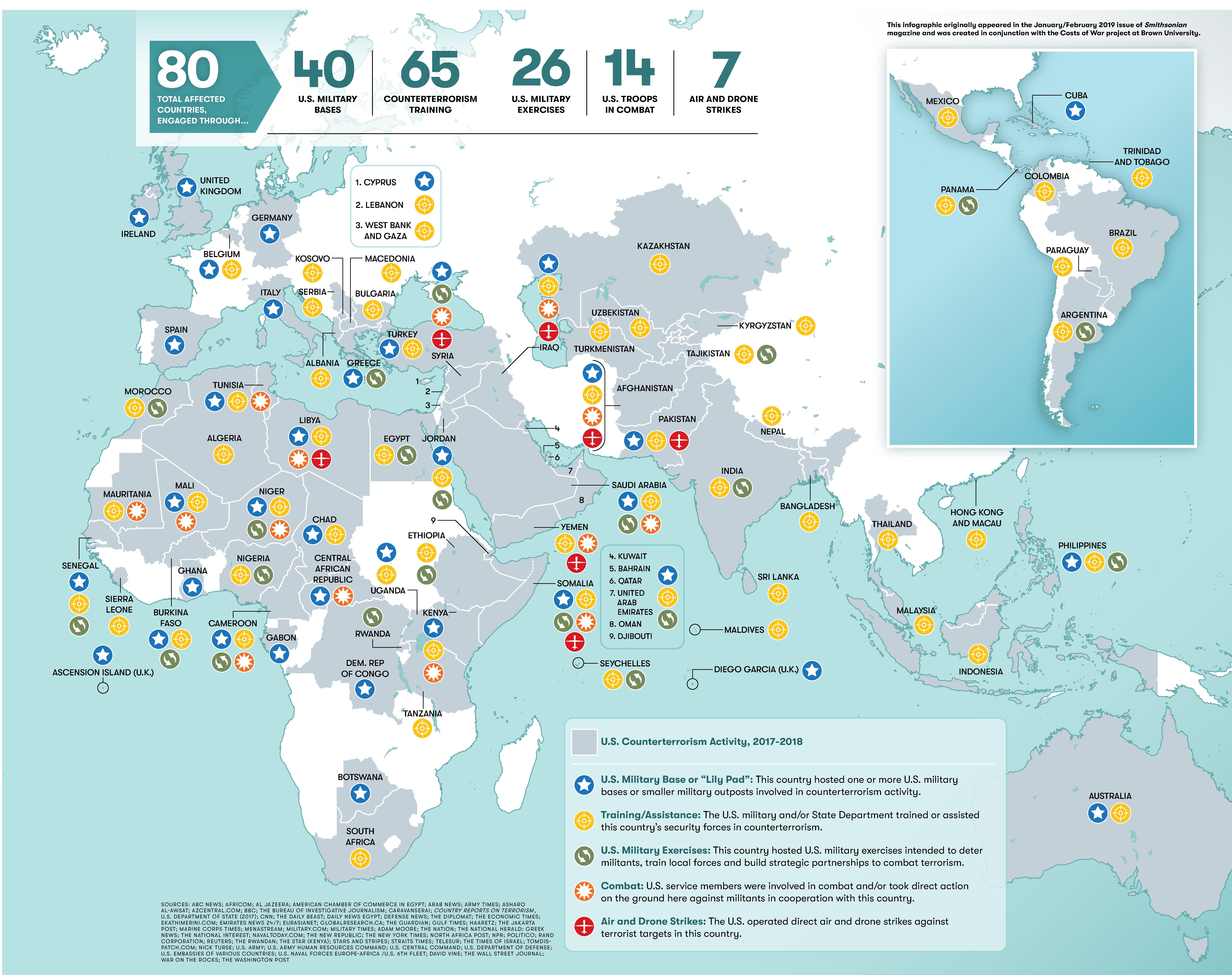

So, why does the United States maintain troops in at least 175 countries, and roughly 1,000 major military bases in over 80 countries outside the United States and its colonies? This is a practice whose development depended on racism. When old-fashioned colonies became unnecessary for rubber, tin, and other materials that chemists could create, the exception of oil remained, and the desire to maintain troops near potential new wars (however progressively marketed) remained. Now that it is clear to most of us that oil will render the earth uninhabitable, that the United States can get its planes, ships, drones, and troops to any spot on earth rapidly without any nearby base, and that all human beings are equally capable of creating such splendorous monuments to self-government as the campaign ad, the gerrymandered district, and the unverifiable voting machine, it’s mostly the belief that non-U.S. people don’t matter that remains.

Savell, Stephanie. 2019. “Where We Fight.” Costs of War Project, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University. Graphic designed and published by Smithsonian magazine, January/February 2019.

There are profits to be made, and weapons-buying or oil-selling or labor-exploiting dictatorships to be propped up. There’s the inertia of the way things are. There’s the perverse drive to dominate the globe. But the marketing scheme for the global archipelago of bases comes down to the need to police people for their own good, even though they mostly believe it harms them. The presence of not a single foreign U.S. or NATO base has been approved by a public referendum. Numerous such bases have been voted down by public referenda (including one in February 2019 in Okinawa), not a single one of which has been honored by the U.S. government. Many bases are the targets of massive nonviolent protests even before their construction, and for years or decades after.

Most bases are gated communities on steroids. The residents can come out, visit brothels, drink, crash their cars and sometimes airplanes, and commit crimes immune from local prosecution. The bases can emit pollutants and poisons, render the local drinking water deadly, and answer to nobody in the nation being “served” by the base. Those who live outside the base, unless employed there, cannot come in to visit the Little America built inside the walls: the supermarkets, fast food restaurants, schools, gyms, hospitals, childcare centers, golf courses.

An empire of bases is an empire of very little land, but it is no more land that was “available” than the Americas were empty and awaiting European “discovery.” Countless villages and farms have been eradicated, populations evicted from islands, those islands bombed and poisoned into uninhabitability. This process describes significant portions of Hawaii, of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, Bikini Atoll, Enewetak Atoll, Lib Island, Kwajalein Atoll, Ebeye, Vieques, Culebra, Okinawa, Thule, Diego Garcia, and other locations most people in the United States have never heard of. South Korea has evicted large numbers of people from their homes to make way for U.S. bases in recent years. Pagan Island is a new target for destruction.

While the rest of the world’s nations combined have only a few dozen military bases outside their borders, and while the wealthier nations of the world are leaving the United States behind in health, happiness, life expectancy, education, and other measures of well-being, the United States goes right on building and maintaining more bases around the world at great expense (over $100 billion every year), and at great risk. This has been true during every recent U.S. presidency. President Donald Trump may yet get a big new base named for him in Poland, though it is in Asia and Africa that the heaviest base construction is under way.

Bases hold missiles as well as troops, and new bases in Romania and elsewhere have contributed to the highest ever risk of nuclear apocalypse. Bases have generated, motivated, and served as training grounds for terrorism, including such famous terrorist attacks as those of 9-11, driven by opposition to bases in Saudi Arabia, and groups like ISIS, organized in prison camps at U.S. bases in Iraq. An explicit purpose in launching and continuing many wars, including those on Afghanistan and Iraq, is to establish bases. Bases are also used as locations to torture people ostensibly outside the rule of any law. When Congress members suspect that U.S. troops might someday leave Syria or South Korea, they are quick to insist upon a permanent presence, though they are somewhat mollified when White House officials suggest that any troops leaving Syria will only make it as far as Iraq, from which they will be able to quickly attack Iran as “needed.”

The good news is that sometimes people can shut down bases, as when farmers in Japan prevented the construction of a U.S. base in 1957, or when the people of Puerto Rico kicked the U.S. Navy out of Culebra in 1974, and after years of effort, out of Vieques in 2003. Native Americans evicted a Canadian military base from their land in 2013. People of the Marshall Islands shortened a U.S. base lease in 1983. The people of the Philippines kicked out all U.S. bases in 1992 (though the U.S. later returned). A women’s peace camp helped get U.S. missiles out of England in 1993. U.S. bases left Midway Island in 1993 and Bermuda in 1995. Hawaiians won back an island in 2003. In 2007 localities in the Czech Republic held referenda that matched national opinion polls and demonstrations; their opposition moved their government to refuse to host a U.S. base. Saudi Arabia closed its U.S. bases in 2003 (later reopened), as did Uzbekistan in 2005, Kyrgyzstan in 2009. The U.S. military decided it had done enough damage to Johnston/Kalama Atoll in 2004. In 2007, the President of Ecuador answered public demand, and exposed hypocrisy, by announcing the United States would need to host an Ecuadorian base or shut down its base in Ecuador.

There have been many incomplete victories. In Okinawa, when one base is blocked, another is proposed. But a broad and global movement is being built that is sharing strategies and providing assistance across borders. At World BEYOND War, we are putting a major focus on this effort, and have helped to start up a D.C. insider coalition called Overseas Base Realignment and Closure Coalition, drawing heavily on the work of David Vine and his book Base Nation. We’ve also been part of launching a global activist coalition to educate and mobilize people for the closure of U.S. and NATO military bases. This effort has produced a conference in Baltimore, Maryland, in January 2018, and one in Dublin, Ireland, in November 2018.

Some of the angles finding traction and being shared around the world are environmental. U.S. bases are poisoning groundwater, not just all over the United States, where the Pentagon is seeking to legalize such practices, but all over the world, where it needn’t bother. The reasons the Pentagon needn’t bother legalizing destruction abroad ultimately depend on the last remaining widely accepted bigotry in U.S. culture, namely that against every non-U.S. culture.

As the anti-base movement grows, it must work with activists who oppose Western Empire without opposing violence. Spreading the skills of nonviolent activism will be crucial. It must also figure out how to work with that uniquely U.S.-ian creation: libertarianism. One way might be this: Encourage pressure on Trump to continue demanding that nations occupied by (or “hosting”) U.S. bases pay larger fees for the “service.” We can do this while encouraging governments around the world to respond with a polite, “Don’t let the door hit you on your way out.”

At the same time, we cannot lose track of the new world that would be made possible by moving resources away from the maintenance of bases, and away from the even more costly wars they instigate. With this kind of money, the United States could transform both itself and global foreign aid.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America