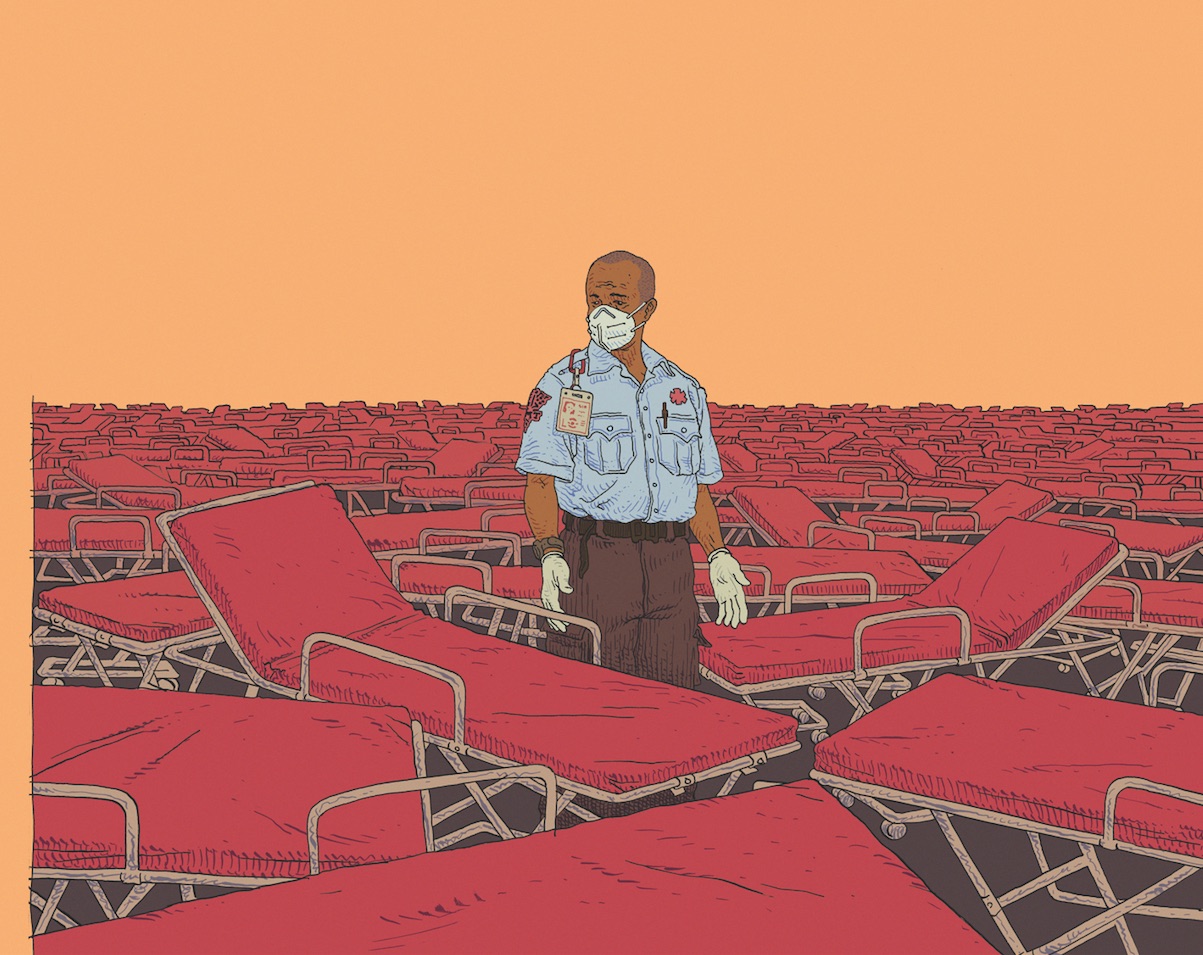

MEDICAL FRONT LINE | An EMT’s Story

Most people who find out I’m an emergency medical technician think I’m first on the scene, saving lives, that sort of thing. There are people who do that, but that’s not my job. I, like most EMTs, don’t respond to 911 calls. We work for private companies, doing interfacility transports. On paper, it’s things like bringing a psych patient from the emergency room to a mental health care center, or a heart attack victim to a hospital equipped for specialized surgery. In reality, it mostly means dumping patients—taking them from the pristine ERs of the private hospitals to the overstuffed, understaffed community hospitals that their health insurance (or lack thereof) actually covers.

On paper, there’s supposed to be a medical reason for an ambulance ride to a different facility, or the patient’s insurance won’t cover the trip. The majority of our on-the-job training is learning which keywords to use (like “requires special positioning”) in our documentation, regardless of whether it’s true or not. If the insurance refuses to cover the ambulance trip, then the patient is stuck with the bill. No matter what, my company gets paid. Legally, the patient is allowed to decline the ride, but that would mean saying no first to their nurse, then to us, then listening to us explain everything that could go wrong if they don’t shut up, sign the paperwork, and accept the ride. Most EMTs don’t tell people about their right to refuse care—if a patient refuses care and later their condition gets worse, we can be sued and lose our licenses if our documentation isn’t perfect. I make $15 an hour. In July 2021, I’ll get a $0.30 raise. I don’t make enough to take that kind of risk.

Emergency Medical Services is a small-picture field. It deals in proximate causes. I have anecdotes, not statistics. Here’s one:

“If I had known that they were going to send an ambulance, I never would have called,” our patient says. Her private health insurance offers a remote nursing hotline for non-emergency medical transport, but keeps the details opaque, likely for this reason. They heard her report a high blood pressure event and called us in, probably to cover their asses just in case. My partner and I make awkward eye contact over our gurney. We had been excited to get this house call, because, unlike our usual runs, these tend to involve doing some actual medicine. I take her blood pressure; it’s in the high 190s. The woman clearly needs to see a doctor.

“How much are they going to charge me for this?” she asks. Neither of us has an answer to that question. Eventually we get her to come with us. We’re all in agreement that she doesn’t need an ambulance for this, but the rules say we have to strap her onto our gurney anyway. She has the right to tell us to go away—we can’t force her to go if she doesn’t want to—but if either of us tells her so, we could lose our jobs. All she talks about on the journey is how she can’t afford this. Her blood pressure climbs into the 200s, probably from the stress. Who have we really helped here? We take her to the ER, and the ER takes her as a patient, because we’re all covering our asses. Lost in the shuffle of lab and legal and billing paperwork is what our patient actually wants, what she can actually afford.

We bandage a person’s infected foot wound, an injury caused by years of untreated diabetes.

We transport an unhoused person to an ER to treat their psychotic episode, sure that months of living on the street without medication were what made their situation bad enough to require an ambulance.

No matter how fast our ambulance gets to the scene, it arrives months and years too late to do any good. As capitalism leaves more and more people behind, EMTs and paramedics will be the ones to respond to its failures, from health management to malnutrition to homelessness. And, given the politics of many of those working in emergency services, it’s likely that this strain will breed hostility rather than solidarity.

At the time of this writing, my county has issued new instructions to ambulance crews: Because ERs are so overcrowded with COVID-19 patients, people in cardiac arrest are not to be transported. If we can’t resuscitate them on scene, we declare them dead.

Prior to getting that directive, I had planned to end by saying that our healthcare system is unwilling to let anybody die, but it’s unable to truly help them live. The pandemic hasn’t changed this equation, only exposed the fault lines that were already there. Until our ability to stay healthy is uncoupled from our ability to produce profit, the logo on your health insurance card (if you have one) largely determines your fate.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America