BOOK REVIEW | Italy: Personalities Preempt Politics

Does Italy’s often bewildering political volatility contain any lessons for the Left?

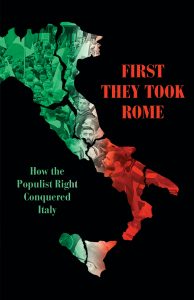

David Broder believes it does. In First They Took Rome (Verso), the Europe editor of Jacobin magazine argues that Italian politics may be less the exception than the rule in the future. He sees Italy’s political fragmentation over the past 30 years as a national case study of a larger globalized pattern. Broder is here to tell us how this came to be and what lessons we can draw from it.

Broder argues that the collapse of the mass parties of both Left and Right that structured postwar Italy led to their replacement by an ever-shifting sea of media- and personality-driven political groupings. Previously, the right-Catholic Christian Democracy party had held continuous national political power. In perennial opposition—but always excluded from national government—was the massive Italian Communist Party. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 ended this Cold War divide, thereby opening a new era for Italian politics.

This historic shift led to the domination of Italy’s political system by such figures and formations as billionaire Silvio Berlusconi (a businessman with no prior political experience who has been prime minister in four different governments), Matteo Salvini’s far-right Lega Party, and the ever-amorphous Five Star Movement (M5S). Broder traces their histories, analyzes their developments, and locates their social bases in Italian society.

Despite dominating Italian politics for more than a decade, Berlusconi plays the smallest role in the overall story. His Forza Italia political party is today a shell of its former self. Instead, it is now the anti-migrant Lega (previously Lega Nord, reflecting its northern-separatist origins) that is the leading right-wing party, somewhat ironically capturing the rural-southern vote in the process. The “neither left nor right” M5S, on the other hand, has made significant inroads into the historic voting base of the Italian Left.

Broder argues that, despite their many differences, both Lega and M5S share a common “anti-political” project. Each reflects an explicit turn away from the realm of formal politics. This is in sharp contrast to Italy’s previous system of mass parties, where each membership-based party sought to use electoral campaigns to organize a broader civil society, albeit often corruptly.

Today, Italy’s populists place themselves in conscious opposition to party-organized politics, what they term the partitocrazia or the political “caste.” This is in part a legitimate reaction to the wave of corruption scandals in the early 1990s that led to the collapse of Italy’s existing party system. But, as Broder notes, it also reflects a deeper and more troubling distrust among many Italians in the ability of political action to solve society’s problems.

For Broder, this loss of faith in collective political action makes Italy a symbol of our present condition. The trends themselves are global: depoliticization, rising inequality, falling public investment, and growing social atomization. But in Italy, the political manifestation of these neoliberal trends has taken on a particularly acute form. First They Took Rome presents a compelling story of the dangers that arise when mass political parties are removed from public life.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America