Marx and Debs on the Big Screen

With the possible exceptions of Sergei Eisenstein’s early odes to the Russian revolutions and Herbert Biberman’s 1954 strike anthem Salt of the Earth, the last time U.S. audiences saw a big-screen testament to socialism may have been Reds, in 1981. But with the appearance of two new films—one a taut melodrama on Karl Marx’s formative years and the other a blistering documentary on the life of Eugene V. Debs—the drought may be ending.

With the possible exceptions of Sergei Eisenstein’s early odes to the Russian revolutions and Herbert Biberman’s 1954 strike anthem Salt of the Earth, the last time U.S. audiences saw a big-screen testament to socialism may have been Reds, in 1981. But with the appearance of two new films—one a taut melodrama on Karl Marx’s formative years and the other a blistering documentary on the life of Eugene V. Debs—the drought may be ending.

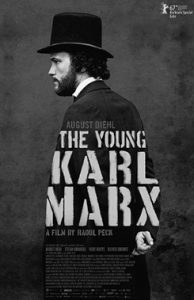

Raoul Peck’s The Young Karl Marx brings to a mass audience not just the revolutionary ideas of Marx and his friend and collaborator Frederick Engels, but an approach to politics and history that still has no peer. Charting the world as he saw it, Marx wrote, “Accumulation of wealth at one pole is at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole.” Has anything changed?

The film, taking up its story in 1844, follows two young men who challenged not only leading thinkers of the academy but also radicals removed from real struggles. It ends with the publication of “The Communist Manifesto” in 1848, when neither of the authors was yet 30 years old.

Heavily influenced by the German philosophers Georg W.F. Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach, the duo created not just a philosophy but a politics. They took from Hegel the idea of the dialectic as a clash of opposites leading to a synthesis and applied it to institutions and movements as a framework for action through understanding power and powerlessness. From Feuerbach, they adopted the idea of reality as materially based, though reliant on human will and activity.

Unlike the era’s utopian socialists, Marx and Engels based their politics on a reading of economic relations in which the dominant culture does not determine economic facts on the ground; rather it is the relations of production that shape the state and its politics.

The film’s treatment of factory worker Mary Burns, Engels’ longtime lover and part of the group that helped him investigate conditions among Manchester’s poor, is a pleasant surprise. Although it posits Burns as a dissident worker at Engels’ father’s factory—for which there is no known evidence—it presents her as a self-directed militant at a time when women in the workforce were invisible to scholars and journalists. It also counters the usual treatment of Burns, whom historians often either ignore or mention in a snarky aside, given that she and Engels never married.

Peck, who also directed the feature film Lumumba and the documentary I Am Not Your Negro, which profiled James Baldwin, has said, “From the outset, I decided to make a film that would speak to the widest audience, without distorting historical truth.” He keeps his word.

American Socialist

Another film with no distortion is documentary film director Yale Strom’s American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs. It is a faithful and much-needed appraisal of the militant labor leader, five-time Socialist Party presidential candidate, and class-war prisoner jailed for opposing U.S. entry into the First World War. Debs was a fiery, moral force in a corrupted era, and his legacy is well served by the new production. In examining Debs’s biography, the film joins the highly praised but less-well-distributed 1979 Debs documentary by then little-known Bernie Sanders.

Another film with no distortion is documentary film director Yale Strom’s American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs. It is a faithful and much-needed appraisal of the militant labor leader, five-time Socialist Party presidential candidate, and class-war prisoner jailed for opposing U.S. entry into the First World War. Debs was a fiery, moral force in a corrupted era, and his legacy is well served by the new production. In examining Debs’s biography, the film joins the highly praised but less-well-distributed 1979 Debs documentary by then little-known Bernie Sanders.

Debs was among the greatest orators this nation ever produced, yet no recording of his voice survives. Even foreign-language speakers were won over, with many testifying that Debs’s mannerisms alone were magnetic, his fist smacking his palm as he offered such injunctions as, “Progress is born out of agitation. It is agitation or stagnation.”

The film makes clear that Debs, a strong railroad worker-unionist, didn’t start out as a socialist; that transformation came after Grover Cleveland broke the 1894 American Railway Union strike using the mendacious claim that strikers were sabotaging mail delivery. Debs, the union president, went to prison a militant trade unionist and, courtesy of a prison-cell reading of Marx’s Capital, came out six months later a committed revolutionary, though of a discernibly homegrown type. He would, for example, define socialism as “Christianity in action.” For Debs’s religiously inclined listeners, greed and the pursuit of personal wealth were presented as sin.

It was the Socialist Party’s principled opposition to the First World War as an imperialist war and a thinly disguised land grab that led to its undoing and to a five-year prison sentence for Debs under the administration of the ostensibly liberal Woodrow Wilson. Debs’s crime: violating a 1917 Espionage Act provision against urging young men to evade the draft.

On July 16, 1918, Debs was in Canton, Ohio, to address the Ohio Socialist Party’s state convention and visit comrades jailed for speaking out against the war. “I must be exceedingly careful,” he told the convention delegates, “prudent as to what I say….but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in prison than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”

Government stenographers in the crowd noted his comments selectively. Prison followed, due to the alleged danger that his remarks, those of a known “agitator,” posed to troop recruitment—and this just months before the Treaty of Versailles was signed. A red scare followed the war. Foreign radicals were rounded up and deported. Native-born leftists of any stripe were imprisoned.

Running for president on the Socialist ticket in 1920 while incarcerated, Debs garnered just under a million votes. Even as late as 1921, on the eve of leaving office, Woodrow Wilson refused to pardon Debs. It was the GOP’s Warren Harding who granted Debs and 23 others a Christmas commutation.

Although he was a hero to many, Debs did not seek adulation. As he put it in 1906 to an audience of workers in Detroit: “I would not be a Moses to lead you into the Promised Land, because if I could lead you into it, someone else could lead you out of it. You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition.”

His was a U.S. variant of Marx’s insistence on working-class self-activity, that the emancipation of working people was not the prerogative of elites no matter how well-intentioned, but a task largely of the workers alone. Debs’s often quoted statement to his trial judge makes much the same point:

“Years ago, I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class I am in it; while there is a criminal class I am of it; while there is a soul in prison I am not free.”

Debs’s heroes were not the great and good, but the ordinary people who showed uncommon bravery and solidarity with one another, often under extraordinary and intolerable conditions.

Marx and Debs may not yet be household names for the majority in this country, but these films serve as vivid introductions. View them and talk them up. ϖ

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America