Peace, Palestine, and Me

An Israeli Jew looks back on 30 years of fighting for peace and justice for Palestinians

I grew up near Tel Aviv and came of age in the years before the First Intifada began, in 1987. Looking back on over 30 years of activism in support of peace between Israelis and Palestinians, you’d think that I’d know better how to advise comrades about Palestine. But these days, while I have plenty of opinions to offer, I wouldn’t call any of them an ‘answer.’ As a DSA member with firsthand experience on the topic, let me share some of the questions I find most interesting.

Twenty years ago, I was eating fresh fish in the old Yaffa port with one of my best friends, a Palestinian-Israeli Bedouin from Ramle. His tribe had been resettled to the ruins of a depopulated Palestinian town after the 1948 war. We made this pledge: that for us the struggle would never end until our children could look up at a flag, and feel that it represented all of them. It was natural for us to have a politics that made room for two national stories, two groups formerly in conflict, but living not only in a shared state, but a shared society.

First memory: In 2001, I participated in a militant demonstration in East Jerusalem against the construction of the separation barrier, often called “‘the Apartheid Wall.” There were thousands of us, including Israelis, both Jewish and Palestinian, and many “internationals” (a blanket term for folks from overseas doing Palestinian solidarity).

We were teargassed, and some of us climbed to the side to rest for a bit. A foreign journalist approached me and an older man wearing traditional Palestinian garb. The old man didn’t speak English, and the journalist didn’t speak Hebrew, so I was asked to translate between the two of them, using Hebrew with the Palestinian and English with the journalist. It went something like this:

- The journalist: How do you think the conflict can be resolved?

- The Palestinian: God willing, all the Jews will be removed from Palestine and then we can have peace.

The journalist’s eyes opened wide, suddenly very nervous, as if she had inadvertently provoked conflict between me and a local Palestinian elder. But it wasn’t like that at all. He and I nodded to each other knowingly, and I repeated his answer faithfully. Then I added to the journalist, “This is normal. Don’t worry. It’s fine.”

Of course, it is normal, I’m still not worried, and nothing is fine. The elder and I shook hands when the short interview was over. And I climbed down to inhale some more tear gas.

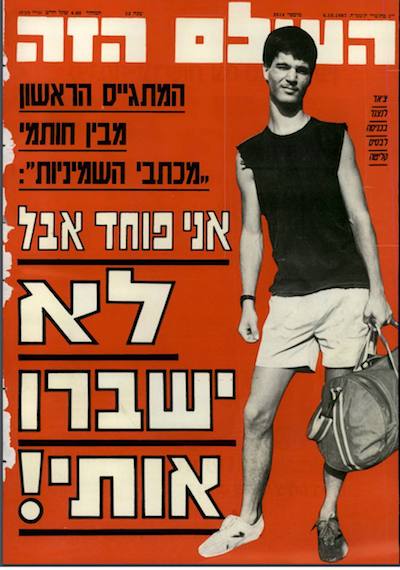

Charles Lechner was the first Israeli to be imprisoned for refusing military service during the Palestinian uprising known as the Intifada. The cover of this 1987 issue of the left-wing tabloid HaOlamOzeh shows him arriving at the induction center.

Second memory: During my first time in military prison, I was a publicized mini-celebrity: the first refusenik of the Intifada, leading a group of young people organized to promote dissent and conscientious refusal in the Occupied Territories.

The second time, instead of saying a loud “no” in the face of being sent to the West Bank, I went AWOL because I couldn’t take it anymore. The awful news blasting on the radio every hour, on the hour, with news of how my side was putting down a popular uprising with great brutality, sapped my ability to deal with my life as a soldier. After a few days I turned myself in and told my officer I didn’t want to obey orders any more.

A few days after that I’m settling in to a particular part of Prison #6, part of the Tzrifin mega-base. I tell the officer in charge that I refuse to do work as a prisoner, because, well, I don’t want to help them. I want to be a burden. The officer speaks to me as to the mentally unwell.

“You aren’t in the press. No one cares. Especially not the Palestinians. Why do this to yourself?”

“I’m not doing this for the Palestinians. I’m doing this because the occupation is evil, like a cancer, it infects everything. Through refusal I can do better.”

And this was true. I wasn’t doing it for the Palestinians. Making sure that an Israel can exist, that Israelis can exist, on a moral plane far above the corrupt reality is a firm opinion held not just by me, but my refusenik partners and the larger movement against the Occupation.

Sometimes, after participating in a Palestine solidarity action in the United States, I think to myself: Actually, I’m doing this because I’m an Israeli who cares about Israel, just as in the United States, many protested the war in Iraq, a criminal enterprise that would kill many for the benefit of a very few, knowing that the war was a U.S. war, and so its citizens must try to stop it.

Back home I belonged to the political ecosystem around Hadash, the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality. It’s a coalition led by the Communist Party of Israel, which is the legacy organization of Communists in Palestine since before 1948. Hadash’s voting base and membership is overwhelmingly Palestinian-Israeli, which meant that my Jewish comrades and I were acting as a minority group inside an “Arab” party.

In one 1980s May Day parade, Hadash would march in Tel-Aviv with red flags and Israeli flags. I didn’t want to carry the Israeli flag, symbol of Zionism and occupation. I got to carry the red flag. My Palestinian friends from Yaffa, Ramle and Lod got to carry the Israeli flags. Some racists starting yelling slurs at the Arabs I was marching with. I got so angry I started to yell back. My Arab comrades hushed me and said, “We don’t respond to that shit.” Now that’s some “Jewish privilege” I needed to unlearn.

Years later, I was working for a Palestinian human rights organization founded to protect against human rights violations committed by the Palestinian security services. Our office was in East Jerusalem, in a neighborhood with no Jews. I would often stay overnight in the office to get a lot done, like translate testimony to English.

Two raw testimonies stuck out for me. One was from a prisoner, a supporter of Hamas, talking about being tortured by his interrogators. At one point, one of the interrogators switched from Arabic to Hebrew. You see, both the Hamas supporter and his torturer had been in Israeli prison, under Israeli interrogation. It was a psychological trick to try to demoralize this one prisoner, to have a Palestinian question him, and torture him, in Hebrew. I doubt this was the only time such a thing happened.

The other came from a prisoner’s mother, after she went to see him at the jail. She was led to a waiting area where there was one other person waiting. The man had bandages and bruises, a face full of purple and yellow. She sat there a long time before figuring out that the man was her son.

Those were some long nights. I had spent years fighting for a Palestinian state; was this any kind if victory? How do we measure the advance of Palestinian power under such circumstances? Suddenly none of the categories other people want to hold on to have meaning.

What does it mean to be “Jewish” and have that faith, or ethnic pride, when all around you the symbols of Judaism turn out to be window dressing for occupation and human rights abuses? Then you see all the diseases of occupation—violence, torture, corruption—successfully exported to the Palestinian Authority and to the Gaza prison. Does that mean Israel is winning?

I spent many years working professionally for groups that received grants to advance peace and human rights. One donor network gave a grant to be shared between my group and a Palestinian group, a grant I’d never applied for. It turned out that the other group had forged our name and pretended we were a partner. When I called the entity awarding grants to let them know about the fraud, they asked me: Can’t you just take the money? These were the years I spent telling consuls in East Jerusalem that corruption will destroy the peace process. They would smile and say, “The political situation is very delicate now. We have to focus on security and peace-building.”

More than 20 years ago, I joined what we now call the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) movement, which was back then a campaign by an Israeli group called “Gush Shalom.” They tracked exports from the Occupied Territories to Europe, and tried to get them labeled “from Occupied Territories.” In Israel and in Hebrew, they published the names of companies making consumer goods in the West Bank and Gaza, so that Israelis could boycott them. The goal was to divide Israelis from the Occupation and highlight the “otherness” of the Settler community. Today, a majority of Israelis think the left are the “other.” Settlers? Not so much.

It can be strange sometimes, bringing the baggage from my first political home into the politics of the current moment. What does it mean to focus on dividing Israel from the Occupation? What does it mean to lift up a “Palestinian-Israeli” political party and refuse to let the Israeli state divide Jews from Palestinians? What does it mean that I spent years as a Jewish minority inside a mass Palestinian political party? How do I explain that when I refused military service and went to prison, it was—in part—because I was fighting for an Israeli society that maybe, just maybe, could find a way past occupation. The sad truth is that very few people living in Israel or Palestine feel that way today, and this isn’t going to change on a political timeline.

People of conscience, never mind people with socialist politics, understand that our political influence is for the Palestinians and against the Israeli state and its supporters in the United States. We as DSA embraced BDS as a way to advance the struggle. The U.S. Left is further emboldened by having a Palestinian-American woman in Congress (Rashida Tlaib) and seeing another congresswomen (AOC) call for reducing aid to Israel.

The Palestinian story is being told to more people nowadays. The Israel story is less dominant, and that’s a good thing. It’s likely that the Democratic Party is going to continue its transformation and move away from uncritically supporting Israel and the Occupation.

As for me, I’m not ready to let go completely. Israelis on the socialist Left—Jews and Arabs—have fought courageously for over 70 years for a different kind of Israel, and thus for a different kind of Palestine. It looks like they lost, and things are only getting worse on the ground. That “different kind of Israel” was a prize worth fighting for. For me, it’s fair to mourn the loss, even as we raise the Palestinian flag high.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America