Decriminalizing Sex Work

On April 11 of this year, Donald Trump signed into law two bills that significantly increased the dangers faced by sex workers. The Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) may have sounded as if they were meant to target those who coerce others into the sex trade, but the vague language of the bills has allowed the government to shut down websites used by voluntary sex workers, thus depriving them of ways to vet clients and exposing them to violence.

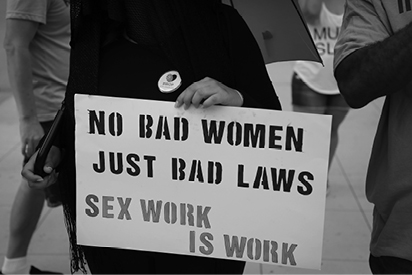

The backlash from sex workers and their allies has been loud, large, and too late. Although individual DSAers worked against the legislation, the national organization did not devote resources to it. I would argue that we must establish ourselves as radical allies of all workers by coming out in full support of decriminalization of sex work. Full decriminalization is a feminist issue, a prison abolitionist issue, and a labor issue, and thus is a natural cause for socialists to support. It means that sex work would be treated as is any other work, subject to fair labor practices.

The backlash from sex workers and their allies has been loud, large, and too late. Although individual DSAers worked against the legislation, the national organization did not devote resources to it. I would argue that we must establish ourselves as radical allies of all workers by coming out in full support of decriminalization of sex work. Full decriminalization is a feminist issue, a prison abolitionist issue, and a labor issue, and thus is a natural cause for socialists to support. It means that sex work would be treated as is any other work, subject to fair labor practices.

One of the major obstacles to sex workers’ rights and decriminalization becoming a mainstream cause for leftist and feminist organizations, both in the United States and abroad, has been the divided opinion among leftists over whether it can truly be “feminist” to support sex work in any way. On one side are those who say that it is useless to distinguish between “voluntary” sex work and “coercive” sex work, as all instances of selling and buying sex are coercive because of the imbalance of power caused by patriarchy. The other side responds that it is inherently anti-feminist to erase the agency of people who engage in sex work of their own free will. As socialists, we know that it is necessary to apply a class analysis to this situation. Patriarchy and capitalism do not exist separately. They are symbiotic. If we recognize that all wage labor under capitalism is inherently coercive, and thus all workers have their agency negated to some extent regardless of gender, then we should ask ourselves how our negative views on sex work versus other forms of wage labor might come from the patriarchal views that have surrounded most of us since birth.

Halfway Measures

A middle way of sorts is what’s known as the Nordic model, in which clients are prosecuted rather than workers. It has been in effect in Sweden and Norway since 1999. In 2016, France enacted law number 2016-444 that similarly intended to criminalize demand instead of supply. A survey of French sex workers the following year showed that 42% experienced an increased exposure to violence and social stigma and 38% found it harder to get clients to use condoms. As we’re seeing now in the United States post-SESTA/FOSTA, because the client pool is smaller, workers are less able to pick and choose, and that leads to workers being forced into riskier and more dangerous situations. Even in countries that have adopted the “end demand” model, workers are still harassed and targeted by police. A 2016 Amnesty International report found that Norwegian sex workers were still being fined for street walking and prosecuted for “brothel keeping” if they chose to share living spaces, a decision motivated by safety in numbers. As Ine Vanwesenbeeck reported in the online Archives of Sexual Behavior, even in the Netherlands, an often cited example of a place with “legalized” sex work, those who try to work outside of the highly regulated and formalized system are still criminalized. Sex workers there are thus still vulnerable to systemic harassment and oppression.

To bring it back to the United States, suspicions of engaging in prostitution are a common pretext for police to harass and intimidate marginalized communities. Transgender people are well aware of the phenomenon of being detained by the police for “walking while trans.” In July 2015, nearly all 200 attendees of a transgender forum in the Bronx reported being profiled by police on the suspicion of prostitution. A court case in 2016 found that Long Beach, California, police intentionally targeted gay men more than any other group in cases of “lewd conduct.”

Policies that Work

There are models that demonstrate the benefits of decriminalization. In 1995, the Australian state of New South Wales decriminalized sex work, then the whole country of New Zealand followed suit in 2003. As today, opponents feared this would cause an explosion in sex trafficking, but the results have been quite the opposite. A follow-up study in New Zealand in 2008 concluded that the sex trade had not only not increased, but more sex workers were able to leave the industry if they so chose, and even felt more encouraged to demand safer conditions. In fact, in 2014, a worker in the city of Wellington successfully sued a brothel owner for NZ$25,000 for sexual harassment. It should be noted, however, that the policies in both New South Wales and Australia still don’t afford protections to non-citizens and migrant sex workers, which is why advocates today specifically demand “FULL decriminalization” in current and future campaigns to close such gaps.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the World Health Organization, Amnesty International, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) have adopted official stances in favor of decriminalization. In fact, the Industrial Workers of the World already organizes sex workers under its public service department as union 690. Although many in the United States may view DSA as the “extreme left,” we have to push ourselves to be bigger players in the worldwide progressive movement and not let our views be constrained by the narrow American political imagination.

Of course, it is not enough to simply make a resolution supporting decriminalization. We must seek actively to welcome sex workers within DSA spaces and give their voices equal weight and priority. Local chapters should work to build coalitions with sex worker advocacy organizations such as the Sex Worker Outreach Project (SWOP), the Desiree Alliance, or the ESPLER Project. The ESPLER project in particular focuses on challenging anti-sex work laws through litigation, such as the ESPLERP vs. Gascon case in California which challenged 647b of the state penal code criminalizing sex work on the grounds that it violated privacy. The case was dismissed at the beginning of this year, but more such cases will arise and may succeed if brought to more people’s attention.

When sex workers are fighting, we need to show up and stand in solidarity as we have done with others. Treating sex workers as comrades does not mean simply inviting them into our spaces, but actively and enthusiastically listening to them and letting them lead the way in the fights that affect them. It means looking at our own internalized attitudes toward sex work. We will only grow as an organization and as a movement if we actively embrace all of those who have been rejected and cast out by capitalism, and this is just the next step.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America