Socialism, Internationalism, Feminism: A 50-Year Journey

Vivian Rothstein Speaks with Maxine Phillips

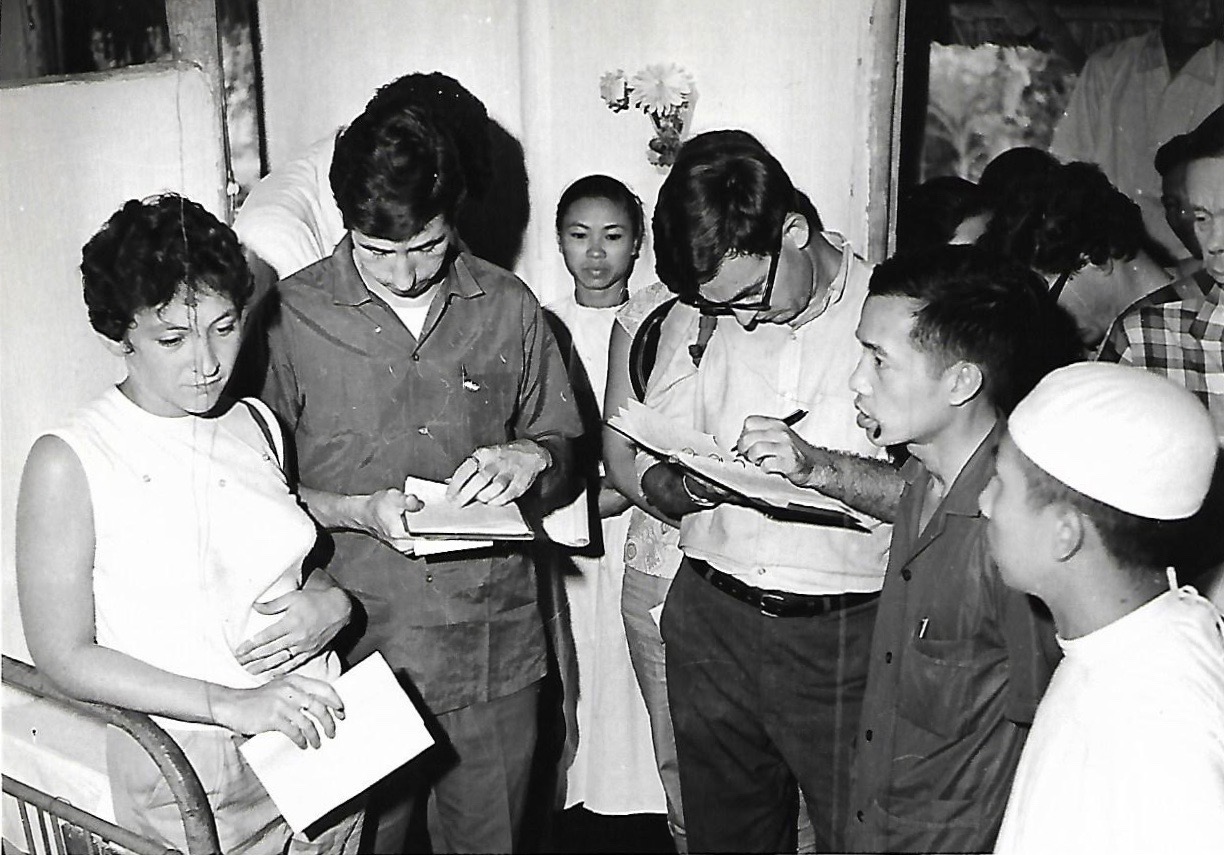

Vivian Rothstein was a Mississippi Freedom Summer volunteer in 1965 and later a community organizer in Uptown Chicago. In 1967, she participated in a peace delegation to North Vietnam to bear witness to the U.S. bombing of civilian targets. Upon returning to the United States, she helped organize the Jeannette Rankin Brigade, which, in January 1968, held the first national women’s march against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. Rothstein also helped arrange subsequent meetings between U.S. and Vietnamese women to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

In 1968, she helped found the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU), one of the first, multi-issue, women’s liberation organizations. For the past 20 years, she has been involved with the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE) and Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (CLUE), working to lift standards for low-wage workers in Southern California. For this interview, she answered questions by email about what she learned from her antiwar activism.

What were the influences that pushed you to political involvement and then to anti-war work?

My parents’ experience as German-Jewish refugees during WWII made me aware of the power of political oppression and the extreme dangers that minority groups can face from a political system. I was drawn to the civil rights movement as a college student, and as the Vietnam War escalated, it became clear that the target of the war, the Vietnamese people, were poor people determined to win their independence from domination by outside nations. I felt an identity and sympathy with their struggle.

What conditions did antiwar activists face then and how do those differ from what activists face today?

The universal draft initially caused a broad spectrum of Americans to question the sacrifices being made to wage a war that few felt any connection to. With deferments available to students and other more privileged people, the class nature of the sacrifice became clear, and eventually the draft was replaced by a lottery system that was supposed to be fairer but still allowed exceptions for those with powerful connections. Today’s professional army is a very different institution, with people signing up for skills training, to get a college education, and/or for a potential life-long career.

Key progressive journalists during the Vietnam War made heroic efforts to expose the true nature of the war. In addition, the Vietnamese from North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front in South Vietnam fostered connections with U.S. peace activists. They gave us the information, understanding, and firsthand experience of U.S. policy in Vietnam, to counter the claims of the U.S. government. This access to unfiltered information from the «other side» is missing today to a large extent, with journalists «embedded» with military units and restrictions on visits by Americans to war zones. These differences, combined with a professional army, and the increased use of technology, leave most Americans feeling disconnected from the consequences of our government’s military exploits.

What do you wish you had known then that you know now; that is, if you were getting involved now what would you do that was similar and what would be different?

I think we were naïve about the extent of government surveillance and interference in our antiwar activities and attempts to subvert our movements. For the groups that did veer off into what I consider irresponsible violence, I think they should have investigated more critically the goals of the individuals who pushed this strategy. In my mind, we were trying to build a majoritarian movement to end the war, and violence was not the strategy to bring the majority to our side.

How did your ant-war activism shape your life going forward? When you returned from Vietnam, you started organizing with women. Did you see this as a major shift in your thinking or a continuation of what you’d been doing?

Activism became the center of my life, as it was for many others of my generation. In the “movement” I had experiences (such as public speaking, international travel, leadership opportunities, strategy development) that were not readily available to women in the larger culture. I was inspired by women in Mississippi who were grassroots leaders of the powerful local civil rights movement. Yet despite the skills and abilities that many women were developing, it seemed that there were few opportunities for us and for issues of importance to women to be taken seriously in the left organizations of the time.

While traveling in North Vietnam I was introduced to the Vietnamese Women’s Union, which saw its role as educating, training, and promoting women to be full participants in Vietnamese society. Their organization inspired the idea of organizing a similar “Women’s Union” in Chicago.

The life I’ve led as an organizer and activist starting in the 1960s until the present has provided deep personal meaning and satisfaction, and I don’t consider it to have been a sacrifice but a privilege.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America