Lost in the Wilderness: Can the White Working Class Return Home?

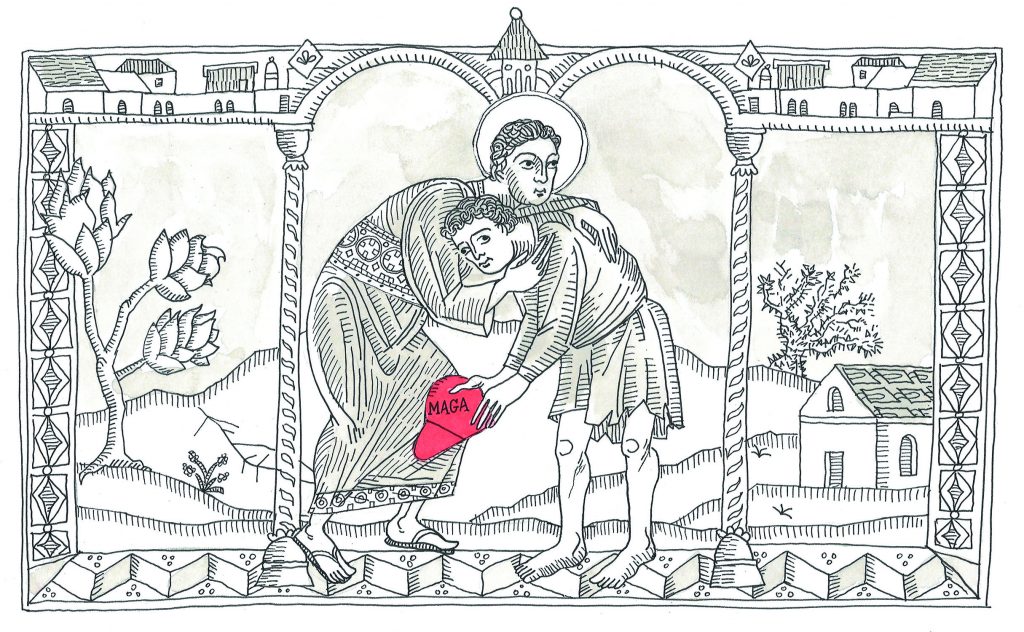

Illustration by Aaron MoDavis

After Joe Biden’s 2020 win, a glaring fact stood out. The United States is a house divided. The wholesale repudiation of Donald Trump did not happen. Many white voters cling to the grievance politics he stoked. At stake is what does whiteness mean today?

The answer is in the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son. The U.S. ruling class used race to divide U.S workers, but now whiteness is becoming an empty inheritance. If the Left can welcome back the repentant Prodigal Sons of his- tory, it can create a social democratic country.

To recap the original story: One son of a rich man took his inheritance early, squandered it, and when famine came, crawled back to his family, ready to take menial work be- cause he was starving. His brother, who had stayed home and been dutiful, was furious. But the father welcomed the errant, repentant adult child.

Dividing the Inheritance

Before America, whiteness did not exist. The early colonial era was a brutal time but not a racial one. In the New World, slaves and indentured servants, Africans and Europeans lived in a limbo. Free Africans could buy land. Europeans could be whipped or branded for disobeying masters.

They worked relentlessly in brutal winters and boiling summers. The sweat of labor glued them together. They were exploited by the same wealthy landowners. When Nathaniel Bacon led a rebellion against Virginia’s colonial government in 1675-76, Africans and Europeans shared musket balls and shot the same English enemy.

The revolt was crushed violently. New laws, written by the ruling class, pitted the two groups against each other. “White” became a privileged identity. The Prodigal Son was born. He was white and male; he got more rights, more land, more status. He felt his power against a Black back- ground. He left the human family.

Today, we live among his descendants. Every wave of European immigrants took up the Prodigal Son’s role. Whether Irish, Jewish from whatever country, Italian, they bought new “white” lives, new faces, new cars, new homes, and new last names. They benefited from the New Deal and the post–Second World War economy. Those who could barricaded themselves in suburbs, recalling the scene from Luke 15:12, when the Prodigal Son “took his journey into high country, and there wasted his substance with riotous living.”

Now, a great famine has struck the West. Capitalism, the engine of whiteness, has left white workers behind. At home, technology has replaced them. Overseas, cheap labor has replaced them. The Prodigal Son has no future.

The Moral See-Saw

In the 2020 election, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won just enough of the white working class to tilt the scales. If they can bring about real reforms, such as universal healthcare and a Green New Deal-type jobs program, those voters will stay. If not, they will turn right again, into a dead end. The GOP will do what the GOP always does: channel anxiety at global elites and minorities while pushing business-friendly policies. More tax cuts. More labor rights repealed.

The problem is that if the white working class goes left, they’ll meet disgust. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt maps liberalism as in part driven by a focus on harm. The Left in essence creates “sacred victims,” he says, and regards those with privilege as “subhuman, monstrous, morally deformed.”

Many of us on the Left feel that way about the Prodi- gal Son. We see him as a straight white male and Christian victimizer who is now the victim of the very forces that gave him power. He took his inheritance. Now he wants sympathy?

Our disgust at the Prodigal Son comes through in our fetishizing of elite political jargon and the near-religious embrace of Afro-pessimism, a philosophy of despair about the condition of African Americans. It saturates colleges and bookstores. It ripples out from colleges, where professors repeat the iconography of victimization. It is our wall to keep the Prodigal Son out.

Parts of the Left are like the older brother in the parable, who in Luke 15:28 was so angered that the feckless brother was welcomed home, that “he would not go in.” What can break down this wall of disgust?

The Celebration

“How do you defuse disgust?” the interviewer asked Haidt at his TED talk. Haidt bobbed his head as if trying to get the right word. “The opposite of disgust is actually love,” he said, “Disgust is about borders. Love is about dissolving walls. Personal relationships are probably the most powerful means we have.”

In the Prodigal Son, that wayward child returns home in rags. Luke 15:20 says his “father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him.” The son apologized for his foolishness, and the father, seeing he suffered, did not punish him but celebrated his son’s homecoming.

Welcoming back a lost child is tradition in the Black free- dom movement, where leaders have turned historical suffering into a bridge to other groups. In his 1988 Democratic National Convention speech, Jesse Jackson said, “Most poor people are not lazy. They are not Black. They are not brown. They are mostly white and female and young. But whether white, Black or brown, a hungry baby’s belly turned inside out is the same color—color it pain, color it hurt, color it agony.” Years later, Cornel West repeated the theme: “White working-class brother, we know you have pain … but we’re asking you to confront the most powerful, not scapegoat the most vulnerable.”

What if this is what our ancestors worked so hard for? They put us in the position to decide the fate of the nation. The centuries-long struggle to transform ourselves from slaves to citizens gave us the authority to define the meaning of our history. We’re not victims. We’re inheritors of a powerful empathy that can rescue others who are being trapped as we were. Maybe we can be the elder brother in the parable who meets the Prodigal Son, the millions of them in this country, and tells them it’s time to rejoin the family.

Writer James Baldwin said in an interview with poet Nikki Giovanni, “For a long time you think, no one has ever suffered the way I suffered. Then you realize … that your suffering does not isolate you, it’s your bridge … so that you bring a little light into their suffering, so they can comprehend it and change it.”

It’s not in the Bible, but I like to think that the older brother went into the house where his sibling sat at the table, trembling with shame. I like to think he bent down, lifted up his brother, and hugged him. I think he felt joy when he did.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America